Geobotany

- When discussing geology, Ohio can be divided into east and west parts. The eastern section of Ohio is characterized by sandstone and shale. Shale, which is a thinly layered rock, is much easier to erode than sandstone, which is a very grainy rock that allows water to seep through it. Over millions of years, this difference has led to the rolling hills seen across eastern Ohio. The western part of Ohio is much more flat, and this is due to the limestone base that characterizes this area. Limestone is a calcium-based rock that is susceptible to erosion, which has led to a flat landscape across western Ohio that is perfect for growing corn and soybeans.

- Over 200 million years ago, the land that is now known as Ohio has a low arc made of sandstone on top, shales in the middle, and limestone on the bottom. The top of this arc was located around western Ohio and has seen the most erosion. This is why limestone characterizes the western part of Ohio. The crest of the arch was exposed to more erosion, which wiped away the sandstone and shale layers of rock. The eastern part of Ohio was not as close to the crest of the arc, and still has layers of sandstone and shales. These layers of rock were eroded by the Teays River and its offshoots, which flowed for 200 million years before the glacial period eventually halted its progress.

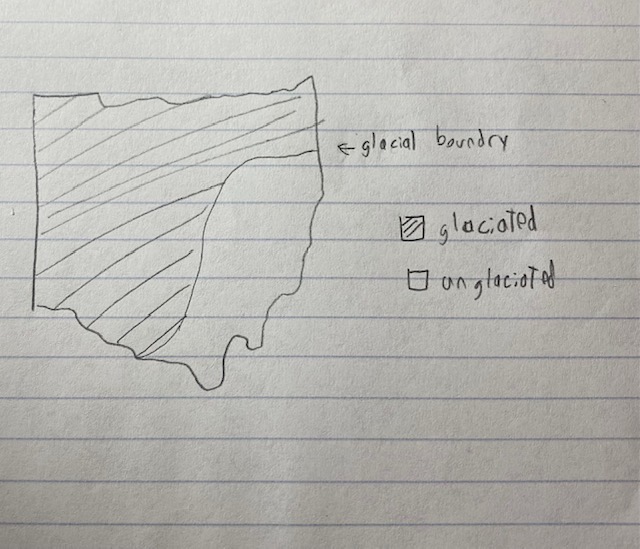

- Hundreds of thousands of years ago, when the glaciers first invaded Ohio they ran into a problem caused by the Teays River. The river had created hills all around eastern Ohio that slowed the path of the glaciers. This is in contrast to the limstone-rich western portion of Ohio, which allowed glaciers to extend beyond Ohio’s south and west borders.

Image of glacial progress through Ohio.

- Glacier till is the process of a glacier depositing different sediment over the area it covers as it melts. This includes sand, silt, and even the gigantic boulders found across Ohio. The till found in western Ohio is full of clay and lime, which came from the glacier moving over the limestone found in this region. Most of the till in eastern Ohio does not contain these sediments except in the areas where the glaciers moved from the limestone region to the sandstone region carrying limestone and clay.

- The differences in bedrock and till have led to particular types of plants that only grow in either western or eastern Ohio. There are a number of factors that explain why this is the case. In western Ohio, the clay till has poor drainage, causing water to build up on top of the surface, which leads to less oxygen being available to the plants. The limey till is alkaline, which leads to a higher pH in this area as well as access to many nutrients. In Eastern Ohio however, nutrients are harder to come by due to the sandstone base. This sandstone base also has a lower pH which causes more acidic soil, and drains water fairly well which leaves hilltops dry but the valleys fairly wet.

- Some trees that are generally limited to limestone or limey substrates:

- Blue Ash (Fraxinus quadranhulata)

- Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

- Fragrant Sumac (Rhus aromatica)

- Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

- Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Blue Ash – opposite pinnately compound and toothed leaves

Northern Hackberry – alternate simple fan-veined leaves that are always toothed. Located in the top right of the picture.

7. Some trees that are generally limited to high-lime, high-clay substrate areas of Ohio:

- Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum)

- Beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- Red Oak (Quercus borealis)

- Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovate)

- White Ash (Fraxinus americana)

8. Some trees and shrubs that are generally limited to the acidic sandstone hills:

- Chestnut Oak (Quercus montana)

- Sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum)

- Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

- Huckleberry-blueberry (Vaccinium ssp.)

- Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia)

9. The major determinant of species is not always simply the type of bedrock the plant is growing over. For example, the distribution of hemlock seems to be more dependent on the environment. Though it likes the limey soil, it can be found in eastern parts of Ohio because it loves a cool moist area to grow in that the sandstone hills can provide. This is different than the sweet buckeye, which is only found in eastern areas of Ohio and never in areas where glaciers used to be. Rhododendron also seems to grow only south of the glacial border, but the reason is different than that of the sweet buckeye. It is believed that this tree migrated to southern Ohio using the Teays River and has lived there ever since.

Cedar Bog (that’s actually a fen)

Cedar bog is a limestone-rich, alkaline-based fen. That’s right, a fen instead of a bog. That means that there are streams that are constantly draining the water out of the area, and allowing new water to flow into the fen carrying limestone. This particular fen called Cedar Bog (this is going to get confusing) is made possible due to valleys carved out by the Teays River I mentioned in the last section. The river, which is now covered up due to the glaciers, still allows water to flow underground and pass through Cedar Bog. All of these things put together are what make this preservation so unique. Now, Cedar Bog is home to many rare alkaline-loving plants that I will love to show you.

But first, here are some pictures of the Cedar Bog landscape:

While I was at Cedar Bog I was asked to find two plants with pinnately compound leaves. The first one I want to show you is rather interesting and dangerous…

Poison Sumac (Toxicodendron vernix)

The Poison Sumac doesn’t look as scary as other poisonous plants like Poison Ivy, but it’s far more dangerous. Simply touching any part of this plant will cause severe irritation to your skin, and breathing in the smoke from burned logs can cause death2. At this point, you’re probably wondering how to identify it so you don’t accidentally stumble upon it. If you want to avoid it, look out for a small tree or shrub with gray thin bark. The leaves will be pinnately compound with reddish stems and entire leaflets. They produce white fruit that grows in clusters during the fall season2. If you’re not sure if it’s Poison Sumac or not, it’s best to avoid it.

The plant is native to eastern North America, but humans tend to avoid it rather than find good uses for it. The exception is that its sap has been used to make a black varnish2. Local wildlife has also found a use for this plant by eating its berries2. It seems to have no toxic effect on woodland creatures.

Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera maackii)

The Amur Honeysuckle is considered an invasive plant species in Ohio. It is characterized by its opposite pinnately compound leaves and wide growth. In spring this plant grows bilateral white flowers that eventually turn yellow1. In the fall it produces a bright red fruit that is eaten by the local wildlife.

This plant was originally brought to North America as an ornamental plant in the late 1800s where it was encouraged to be planted1. It was even used in erosion control due to its roots that take hold of an expansive area of the ground after being planted for a few years1. However, it was discovered that this plant did more harm than good for the ecosystem, and has since been banned from being planted.

I do want to note that this tree was not found at Cedar Bog, but rather in the Cedar Ridge Picnic Area which was a stop on our trip. I did not know that the scavenger hunt was to be done at Cedar Bog, and after I met my quota of two plants with pinnately compound leaves I started taking pictures of more interesting wildflowers.

Wildflowers

Spotted touch-me-not (Impatiens capensis) – CC value of 2

Grass-of-Parnassus (Parnassia glauca) – CC value of 10

Clasping-leaved aster (Symphyotrichum patens) – CC value of 6

Kalm’s lobelia (Lobelia kalmii) – CC value of 9

Thank you for looking at my discoveries at Cedar Bog in the limestone region of Ohio!

References:

(1) Amur Honeysuckle. (n.d.). Woody Invasive of the Great Lakes. https://woodyinvasives.org/woody-invasive-species/amur-honeysuckle/#1562693875822-a414adf0-9858fa11-61a14714-3122

(2) National Audubon Society Trees of North America (1st ed.).(2021). New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.