Ohio is full of trees. In fact, it’s impossible to escape them by any means other than locking yourself inside with the windows boarded up. But why would you want to do that? Trees don’t want to hurt you, though some of them will. That’s why it’s important to learn how to identify them if they’re harmful, and their role in our ecosystem. Ohio has numerous genera of trees and even more species, which can be overwhelming to a new tree hugger. To ease ourselves into learning about them, this page will only have eight different species. Let’s start with the American Sycamore…

Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

This Particular sycamore was found at Griggs Reservoir Park, right next to the Scioto River in an open area. The easiest way to identify this genus of trees is by looking up the trunk of the tree. Notice how the bark starts to peel off as you get further up the tree to the point that the top portion of the tree is bare. The fruit produced by the sycamore tree is also quite distinctive. Those small green balls in the second picture are the fruit. They are composed of many small hairy nuts that turn brown as they mature2.

The arrangement of the leaves is also a good way to identify this tree, as it is with most trees. The leaves of a sycamore alternate down the branch with a simple complexity. The leaflet is lobed with large teeth and has three distinctive veins meeting at the base.

One interesting fact about these trees is they have two natural predators, one is a beetle and the other is a fungus. The beetle is aptly known as a sycamore leaf beetle2. The anthracnose fungus is able to spread from sycomore to sycamore through the wind and lead to sores on these beautiful trees2.

Black Walnut (Juglans nigra)

Now the first thing you may think when looking at the Black Walnut tree is “those walnuts are green, not black you dummy!” You’re right, but if you try to crack open the shell of the fruit to get to the tasty nut you’re hands will be stained black. That along with its darker bark gives it its name. This tree has also adapted to survive by poisoning surrounding trees by secreting chemicals into the soil2. It’s best to plant this tree away from your prized trees.

This tree was also found at Griggs Reservoir Park here in Columbus, Ohio, not far from the bank of the Scioto River. It was more isolated than the other trees, probably due to its toxic effect. The Black Walnut was easily identifiable from the big green fruit growing on it. However, when the fruit is out of season you can look for the alternate pinnately compound leaves that grow many toothed leaflets.

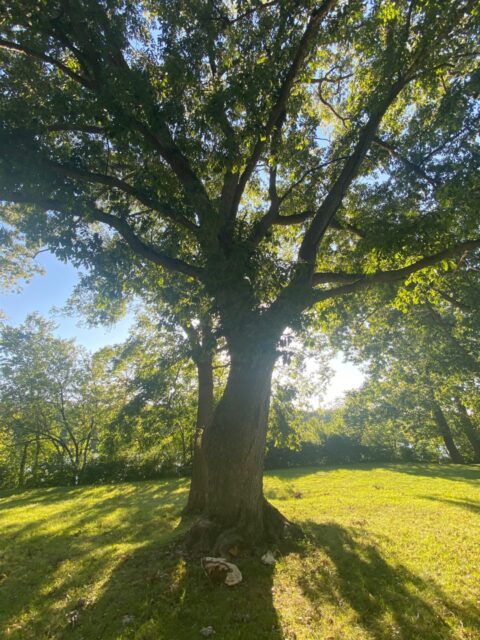

Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii)

Oak trees are scattered all around North America, and Ohio is a popular home to some of those species. The Chinquapin Oak (or Chinkapin Oak) is one of those trees. This tree can be identified by its light gray bark and alternate simple leaves which have large teeth running up the edges. The last picture shows a sprouting acorn which is characteristic of oak trees. This tree was also found in Griggs Reservoir Park standing by itself in the middle of a grasseous near the Scioto River.

The Chinquapin Oak offers a nutrient source of food to many wildlife and many practical uses to humans. During the early days of the United States, these trees were cut down and used as fences throughout Ohio before later being used as fuel to transport trade down Ohio’s rivers1.

Red Oak (Quercus rubra)

Another oak?! Yes, I put another oak, but I have a good reason. Oaks are one of the most abundant tree types in Ohio. When I was taking these photos I saw oak trees in almost every direction. And some are similar enough that it’s difficult to identify between species. This tree, for example, may not be a Quercus rubra as it’s hard to differentiate between species without some important information that isn’t always available. When looking at this tree I was unable to find any fruit, which is almost always a giveaway of the species. But for the time being, I’m going to say this is one of the abundant red oaks.

The Red Oak can be identified by its alternate simple leaves. These leaves are heavily lobed like most oaks but have bristles on the end of each lobe. The tree can be further identified by its dark gray bark and the acorns which grow to have flatter tops than most species3. These trees are able to withstand many different types of weather conditions, allowing them to be transplanted or grown in many different climates throughout eastern North America2. This one was found in Gibbs Resevior Park growing alone.

It might also interest you to know that Red Oaks are poisonious2. So if I really wanted to be sure this was a Quercus rubra all I had to do was eat. I guess I’m not committed enought to identfying tree species.

Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima)

Did it hurt when you fell from heaven? It didn’t hurt this tree since they’re definitely not from heaven. Some people may even suggest that it came from hell since will quickly take over its surrounding, killing nearby plants by secreting tozind into the soil2. This is why they are considered an invasive species, but this wasnt always the case. They were origionally brought to North America from China where they were used as ornamental plants due to their ability to grow fast, but now they can be found in almost every state2.

The Tree-of-hell, wait no. Sorry, I meant Tree-of-heaven can be identified by its alternating lance-shaped pinnately compound leaves. The leaves also appear to be outlined in a white-greenish color that matches the vein. Finally, the leaves have a unique distinction of two teeth near the base on opposite sides of the leave, otherwise, they have smooth edges. The tree is able to grow in almost all climates throughout North America, but this particular one was found within a group of trees at Gribbs Reservoir Park.

Here’s a random fact. The Tree-of-heaven has been used as traditional medicine in Chinese culture2.

Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

The Eastern Redbud is a beautiful ornamental tree when its flowers are in season. Unfortunately, they bloom in early spring, but I did manage to get a few flowers in the pictures. The tree is identified by its heart-shaped leaves which grow in an alternate and with simple complexity. The fruits of the plant are the pods shown in the picture, which will soon cover the ground around the tree. The tree prefers to grow in the eastern climates of North America2. This particular tree was found at Gibbs Reservior Park like the other ones but was growing in a patch of trees. There’s even a bench so you can sit and look at it with deep admiration in the springtime.

Though primarily used as an ornamental tree, it is known that Native Americans used chemicals found in the bark to make medicine2. You could also eat the leaves if you want, which the Native American did as well.

Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina)

The Staghorn Sumac is another popular small ornamental tree. The leaves, which are alternate and pinnately compound, turn a beautiful red in the fall. They can also be identified by their lance shape with many teeth. The name comes from the similarity twigs have in the winter to the antlers on a buck2. The tree’s red fruit grows upright, providing a distinctive shape for identification as well as food to many forms of wildlife. The Native American also used the fruit to make a sweet, sour, and refreshing drink2.

This tree was also found in Gibbs Reservoir Park near clusters of other trees. It’s able to grow in many areas across the northeastern United States and maintains a healthy population2.

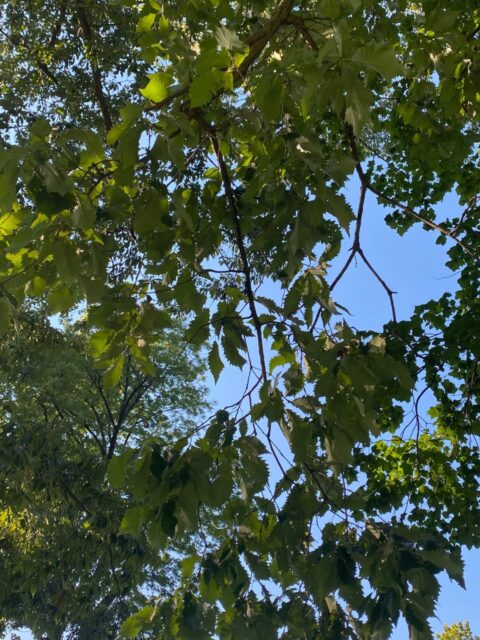

White Mulberry (Morus alba)

Can you guess where I found this last tree? Correct, the Gibbs Reservoir Park! This White Mulberry stood large and proud in an open field toward the east end of the park. These trees don’t need much to grow tall as a mature Morus alba can survive long periods of time without water and do well in warm areas around the United States2. The leaves on this tree are unique since some are lobed and some are entire. They spread out in alternate and simple complexity. The veins of the leaves are distinct and separate in threes from the base, spreading around the teethed leave.

The White Mulberry has a few uses. One comes from the fruit, which is pinkish to white and edible to both humans and wildlife, you can even make it into a wine2. The second use explains why they were introduced to North America. They were introduced in hopes of producing silk commercially through the United States since the trees grow fast and are a choice food for silkworms2.

References:

(1) Arbor Day Foundation. (n.d.). Chinkapin Oak. https://www.arborday.org/trees/treeguide/TreeDetail.cfm?ItemID=875#:~:text=The%20chinkapin%20oak%20is%20also,from%20Pittsburgh%20to%20New%20Orleans.

(2) National Audubon Society Trees of North America (1st ed.).(2021). New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

(3) Petrides, G. A. (1958). A Field Guide to Trees and Shrubs (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin.